by Alex Patton | Apr 1, 2017 | Political Research

I went to bed last night thinking about about DecisionDeskHQ’s attempt to make a nationwide precinct map. It is a challenging and cool project.

Thinking about this as I slumbered, I awoke wondering just ‘how divided are we in Florida at the precinct level’?

Thanks to the great state of Florida, we have precinct level results, and over morning coffee, I found my answer.

The answer: Pretty damn divided.

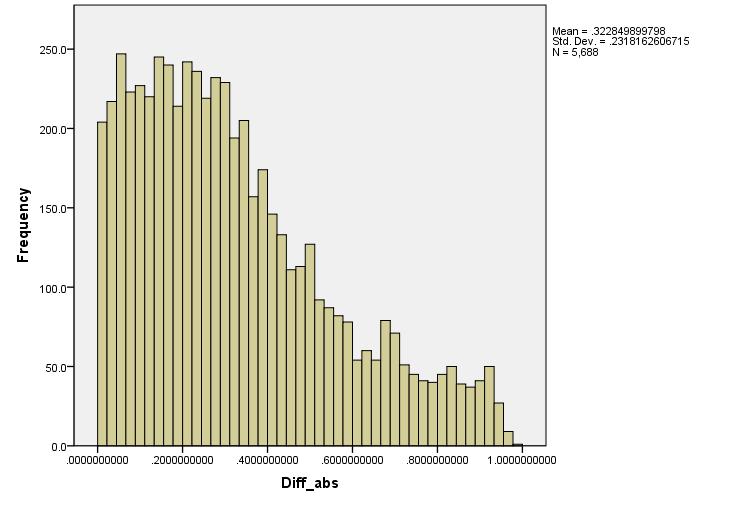

If you consider a precinct “competitive” if separated by 10% or less, then few Floridians live in precincts that are competitive – the median difference in the 2016 POTUS election is 28% in Florida.

Only 18% of Florida’s precincts had Clinton and Trump within 10% of each other.

OR

Almost half (46%) of Florida’s precincts resulted in the difference between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton being greater than or equal to 30%.

P.S. The data is below, and now you know what nerds do on Saturday mornings before their kids wake up.

DATA

This is a histogram of the absolute value of the difference between the Clinton% and Trump% of the vote total.

Note: (I dropped the random precincts that are less than .01 and greater than .99)

Here are the summary statistics:

|

|

Cases |

|

| Valid |

|

Missing |

|

| N |

Percent |

N |

|

| 5688 |

100.00% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Descriptives |

|

|

|

Statistic |

Std. Error |

| Mean |

|

0.32285 |

0.003074 |

| 95% Confidence Interval for Mean |

Lower Bound |

0.316824 |

|

|

Upper Bound |

0.328876 |

|

| 5% Trimmed Mean |

0.309017 |

|

| Median |

|

0.277699 |

|

| Variance |

|

0.054 |

|

| Std. Deviation |

0.231816 |

|

| Minimum |

|

0 |

|

| Maximum |

|

0.982301 |

|

| Range |

|

0.982301 |

|

| Interquartile Range |

0.315587 |

|

| Skewness |

|

0.804 |

0.032 |

| Kurtosis |

|

-0.083 |

0.065 |

Precinct by category

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| 0-10% |

1010 |

17.8 |

17.8 |

| 10-20 |

1033 |

18.2 |

35.9 |

| 20-30 |

1035 |

18.2 |

54.1 |

| 30-40 |

849 |

14.9 |

69 |

| 40-50 |

568 |

10 |

79 |

| 50-60 |

399 |

7 |

86 |

| 60-70 |

286 |

5 |

91.1 |

| 70-80 |

210 |

3.7 |

94.8 |

| 80-90 |

194 |

3.4 |

98.2 |

| 90-100 |

104 |

1.8 |

100 |

| Total |

5688 |

100 |

|

Sum of Votes cast by Precinct Category

| Category |

VotesCast |

% of total |

| 0-10% |

1739609 |

19% |

| 10-20 |

1732374 |

19% |

| 20-30 |

1920034 |

21% |

| 30-40 |

1454646 |

16% |

| 40-50 |

909401 |

10% |

| 50-60 |

578875 |

6% |

| 60-70 |

367632 |

4% |

| 70-80 |

225290 |

2% |

| 80-90 |

228293 |

2% |

| 90-100 |

121634 |

1% |

| Total |

9277788 |

100% |

You can download my cleaned data at: gitHub or at data.world.

by Alex Patton | Feb 11, 2017 | Political Research

I was looking for a data-set this morning for a GIS project, and I thought the data would be relatively easy to find. It wasn’t.

I did find what I wanted in one case, but someone was charging $199 for the data.

So, I spent a couple of hours researching, compiling and cleaning data.

I offer it to you for free and in the name of political analysis. Enjoy!

Data Set: TV DMAs by Counties – USA.

by Alex Patton | Jun 1, 2016 | Political Research

As always, some of the best questions come from readers of the blog. “Why don’t third parties win US presidential elections?” came to us via email.

It is also timely with the recent discussion from Kristol and polling information from Data Targeting.

Polling Third Parties

In a traditional poll, pollsters may ask a question like, “Would you consider supporting a third party candidate? Yes or No?” Traditionally, because the question is asked like this, support for third parties is overstated, and the question has proven to be a poor predictor of voting behavior.

Another way to ask the question is in a horse race question like, “If the election were held today, who would vote for?” Because the answer has no ramifications, again support for third parties is overstated in polling.

So, if people tell pollster they support the idea of an independent candidate then why don’t they actually vote for them? Why do most people vote for their party’s nominee?

History of Third Parties in the US

| YEAR |

PARTY |

CANDIDATE |

VOTE% |

ELECTORAL VOTE |

OUTCOME in Next Election |

| 1832 |

Anti-Masonic |

William Wirt |

7.8% |

7 |

Endorsed Whig Candidate |

| 1848 |

Free Soil |

Martin Van Buren |

10.1 |

0 |

5% of the vote, absorbed by Republican Party |

| 1856 |

Whig-American |

Millard Fillmore |

21.5 |

8 |

Dissolved |

| 1860 |

Southern Democrat |

John C. Breckinridge |

18.1 |

72 |

Dissolved |

| 1860 |

Constitutional Union |

John Bell |

12.6 |

39 |

Dissolved |

| 1892 |

Populist |

James B. Weaver |

8.5 |

22 |

Absorbed by Democratic Party |

| 1912 |

Progressive |

Teddy Roosevelt |

27.5 |

88 |

Returned to Republican Party |

| 1912 |

Socialist |

Eugene V. Debbs |

6.0 |

0 |

Won 3% of the vote |

| 1924 |

Progressive |

Robert M. LaFollette |

16.6 |

13 |

Returned to Republican Party |

| 1948 |

States’ Rights |

Strom Thurmond |

2.4 |

39 |

Dissolved |

| 1948 |

Progressive |

Henry Wallace |

2.4 |

0 |

Won 1.4% of the vote |

| 1968 |

American Independent |

George Wallace |

13.5 |

46 |

Won 1.4% of the vote |

| 1980 |

Independent |

John Anderson |

6.6 |

0 |

Dissolved |

| 1992 |

Reform |

H. Ross Perot |

18.9 |

0 |

Won 8.4% of the vote |

| 1996 |

Reform |

H. Ross Perot |

8.4 |

0 |

Did not run |

| 2000 |

Reform |

Ralph Nader |

2.7 |

0 |

Ran Next election |

| 2004 |

Green |

Ralph Nader |

1.0 |

0 |

— |

Source: http://www.thisnation.com/question/042.html

Research

The authoritative scholar on the issue is Steven Rosenstone at the University of Minnesota.

While there are structural barriers in place for third parties: ballot access, campaign finance laws, polarization of the party elites preventing cross-over third party validators, sparse media coverage, debate exclusion, and the lack of belief that a third party can win, there is a more fundamental way to look at this: the psychology of the voter.

Our political system is dominated by the two party system. Voters operate in primarily in this two party system and many voters take short cuts or cues provided by the parties to simplify their decision making. To step outside the two party system takes considerable effort.

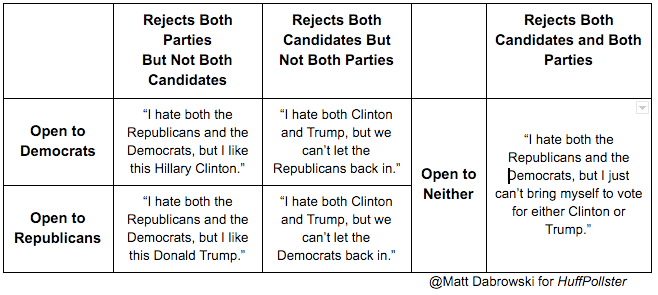

Rosenstone developed a “Four Part Test for Third Party Support” and I believe it provides a framework to answer the question.

On average, for a voter to consider voting for the third party candidate, they have to reject 4 things. Not 2 of 4, but rather all 4. They have to reject both parties’ candidates and both parties, then and only then will they consider a third party. Then the voter has to find a third party candidate they consider to be legitimate and finally, vote for them. A tall task.

Additional Polling

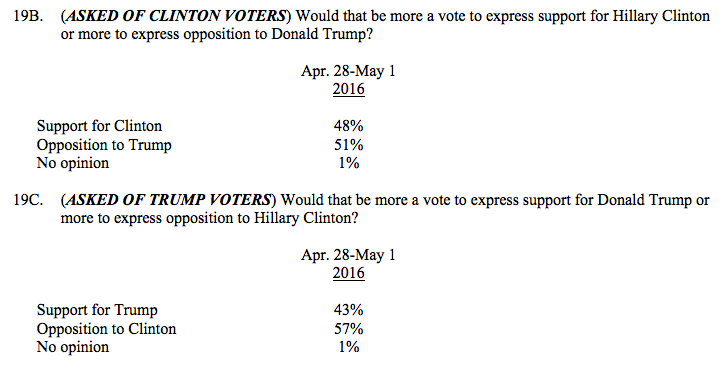

We can see Rosenstone’s framework at work in a CNN poll in May 2016. When respondents were asked if their support for a candidate was an vote of support of opposition, we observe the following: (editor note: quite a sad commentary on our current choices.)

Conclusion

In part, this explains why Donald Trumps’ numbers have improved in the past 4 weeks. His support is growing from Republicans who rejected his primary campaign, but are “coming home” to support the party and/or reject Hillary Clinton/democratic nominee.

In part, this also explains, in part HRC’s soft numbers. The Democrats are still split between HRC and Sanders and have yet to coalesce around a candidate. We should expect the Democratic nominee’s numbers to improve after the voters move through Rosenstone’s framework.

As you can see, third parties have a difficult road ahead of them and the most likely path is not to win, but rather to prevent someone else from winning or the “spoiler” role.

PS – You may be interested in a newer post on this topic: So, You Want to Run As an Independent or Third-Party Candidate?

by Alex Patton | Feb 19, 2016 | Political Research

The sheer number of polls this political cycle is amazing. The sheer number of bad polls this political cycle is stunning.

Regardless, the manner the press reports on polling is just God-awful.

Biggest Polling Complaint

My largest complaint is that the amount of uncertainty in a poll is not reported, is under-reported or misunderstood.

A poll is only a sample (hopefully of a random one that is well constructed) of a population. When any pollster moves from describing the sample to inferring meaning in a population, a known amount of uncertainty is introduced into the results.

The press or most poll consumers are explicitly considering nor communicating the amount of uncertainty in ANY poll.

So here is a quick primer on “How to read a damn political poll”:

Don’t forget the inherent uncertainty in polling

Margin of error – This is the stated uncertainty involved when moving from a description of the sample to an inference towards the population. Often you will see the margin of error expressed as +- x%.

Some often to forget this margin of error is supplying a range of correct answers.

For example, let’s say candidate Ben Smith is polling with high negatives.

52% of the voters in our sample, think Ben Smith is a full on jerk. The margin of error in this survey is the standard +-5%.

This margin of error is a function primarily of the size of the sample – the larger the sample, the smaller the margin of error.

NOTE: Margin of Error does NOT take into consideration or capture errors associated with question order, format, sample error or other factors that could systematically bias a poll.

This means when we move from describing a sample to the population as a whole, ANYWHERE between 47% and 57% of the population think Ben Smith a jerk. Statistics tell us the correct answer is likely within this entire range.

visualizing uncertainty in a poll

We say likely because of the seldom reported confidence intervals.

Confidence Intervals – most of the time, most poll statistics are analyzed at a 95% confidence interval.

This means roughly, if we theoretically repeated this exact poll 100 times, 95 of the 100 times we would expect the real number to be in the range indicated by the margin of error.

HOWEVER, you must also notice 5 out of 100 times our answer could be OUTSIDE the correct range.

Combine both of margin of error and confidence intervals- even before humans are entered into the process – and you see there is uncertainty built into the very framework of polling.

It’s math.

Don’t forget bad polls

Now, let’s consider the human factors.

On top of all inherent uncertainty in ‘perfect’ polling, there are some political and media players taking short cuts in polls compounding errors.

One of the basic prerequisites of good polling is that anyone within your sample frame has an equal and random chance of being selected.

There are two current factors acting on the polling industries:

Response Rate Declines – the polling industry is seeing declining response rates, meaning you’re not answering your phone.

While the research is mixed on the effect of declining response rates with Pew finding in 2012, “despite declining response rates, telephone surveys that include landlines and cell phones and are weighted to match the demographic composition of the population continue to provide accurate data on most political, social and economic measures.” (source: Pew Research)

The Rise of Cell Phones

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, estimated that 39.1% of adults and 47.1% of children lived in wireless-only households. This was 2.8 percentage points higher than the same period in 2012.

This change dis-proportionally affects young people (Nearly two-thirds of 25- to 29-year-olds,) and minorities (Hispanics most likely to be without land line). (source: Pew Research)

The rise of cell phone only homes is problematic for pollsters, because the law forbids pollsters from using automation software to place the calls. This prohibition is a direct cause in the increase of polling costs.

Combination of Response Rates and Cell Phones

We can safely assume these trends of declining response rates and the increasing cell phone only voters continue.

In summary, voters with landlines aren’t answering and reaching cell phone-only voters is expensive. It is this combination that makes good, quality research difficult and expensive.

The media and polling

I loathe to blame the media, but in this case, there may be some justification – the media’s treatment and use of polling results is awful.

Explaining polling is nerdy. The media may report on a poll’s margin of error, but never explains it.

I often asked people what they think ‘margin of error’ means. A sample of replies:

- 5% of the results are wrong

- The results can be off as much as 5%

- Anything within 5% is a statically tie

- We are confident the answer is within 5% of the result

NONE of these are correct. It seems people often forget the ‘plus’ or ‘minus’ part of the stated error.

The media hardly ever states the confidence levels.

The media due to the economics of the news industry wants polling done cheaply. They will use samples that exclude the costly cellphone only homes.

The media due to the nature of news (‘if it bleeds, it leads’) wants the horse race. The need the excitement. They simply can’t have a headline or a report that extolls “the race may or may not be tied, we don’t really know due to uncertainty.”

The bottom line is some media outlets aren’t concerned with accuracy or nuance. Others are cheap include only landline homes, excluding a significant part of the population.

In summary, the media presents results with a level of certainty that doesn’t exist. For example, a presidential candidate is shown to have a 2 point move from last weeks polling numbers. The poll has a +-5% margin of error. In this case scenario, the number is bumping around with the range we would expect. It is nothing more than the expected sampling error.

However, some media would have a headline “Candidate X Surges 2% in Newest Poll”

Lastly, don’t forget purposeful manipulation.

Let’s face it, there are a lot of political operatives and media outlets playing games with polls.

- Only selected results are released

- Questions are purposely written to shade responses

- Awful samples (self-selected) are used and passed off as actual research

- Results are attributed with certainty when it doesn’t exist

These political manipulators understand the powerful effect other peoples’ behavior has on voters. Everyone loves a winner and the herd mentality takes over.

“Candidate X Surges 2% in Newest Poll” is most likely spin from a political operative.

How to read a poll

So as a consumer of a poll, there are some things you can do to increase your understanding of what a poll says and doesn’t say.

STEP 1 – Understand Poll Methodology

Before you read a poll results, read the methodology.

The methodology should tell you how the pollster conducted the poll.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPoR), declares the following items to be disclosed:

- Who sponsored the survey and who conducted the survey,

- Exact wording of questions and response items,

- Definition of population under study,

- Dates of data collection,

- Description of sampling frames, including mention of any segment not covered by design,

- Name of sample supplier,

- Methods used to recruit the panel or participants, if sample from pre-recruited panel or pool,

- Description of the Sample Design,

- Methods or modes used to administer survey and languages used,

- Sample Sizes,

- A description of how weights were calculated,

- Procedures for managing membership, participation and attrition of panel, if panel used,

- Methods of interviewer training, supervision and monitoring if interviews used,

- Details about screening procedures,

- Any relevant stimuli, such as visual or sensory exhibits or show cards,

- Details of any strategies used to help gain cooperation (e.g., advance contact, compensation or incentives, refusal conversion contacts),

- Procedures undertaken to ensure data quality, if any. e. re-contacts to verify information,

- Summaries of the disposition of study-specific sample records so that response rates for probability samples and participation rates for non- probability samples can be computed,

- The unweighted sample size on which one or more reported subgroup estimates are based, and

- Specifications adequate for replication of indices or statistical modeling included in research reports.

Make no mistake, seldom does any political pollster release all this information. (Academics and government surveys often will), but there are some minimal, critical things to consider:

- Sample Size – sample size drives margin of error. The larger the sample, the smaller the MoE.

- Definition of people being studied? Registered versus Likely Voters?

- Sample Frame – how is a pollster defining who has a chance to be polled. Is a prerequisite past voting behavior? Is it simply registered voters? Land line only? Combination? Does Sample Frame match as closely to the Definition as possible? Who is left out?

- Mode(s) used to administer the survey? Telephone type, Internet, door to door? Combination and if so what proportion?

- Is the poll weighted? If so, weighted to what model/universe?

- What is the Margin of Error?

Step 2 – Understand the Polling Demographics

After finding this information, the next is to look at is the Demographics of the poll. Do things look correctly and in proportion?

If you don’t know what the proportions should be for the population you are studying, results presented could be biased.

Due to the importance of partisanship in our political system, take a close look at the partisan breakdown.

If things look off in the demographics, be cautious and skeptical.

Are you looking at weighted numbers? If so, what assumptions are built into the weights?

Step 3 – Look at the Polling Questions

Are the polling questions clear? Are the polling questions loaded with explosive or loaded language?

Are the polling questions not disclosed?

Step 4 – Look at the Polling Credibility Items

What is disclosed?

If NOTHING is disclosed, stop reading the poll or press story. You’ll likely get the same information from reddit.

Does the poll pass the smell test?

Step 5 – Read All Polling Results with skepticism

Finally, if everything so far passes the smell test, then look at the polling results UNDERSTAND that any number presented as a finding has a range of correct answers. I find it helpful to restate a result to make remind myself of the uncertainty inherent in polling.

If a candidate has 40% hard name id with a 5% MOE –

You can state this mentally, “that candidate x is known by 35%-45% of the population studied, AND 65%-55% of the population studied doesn’t recognize him/her. PS – THERE IS STILL A CHANCE THIS IS WRONG.”

Here is the bottom line on Reading Polls:

- Remember, the quality of the polling data will be no better than the most error-prone features of the survey.

- All polling when making inferences of a population contains inherent uncertainty due to fundamental math.

- Polling well is difficult and expensive.

- Always ask yourself, is a political operative attempting to manipulate you?

by Alex Patton | Jul 16, 2015 | Political Consulting, Political Research

This week Politico featured an article The End of the 2016 Election Is Closer Than You Think The Politico article is a fantastic read, but doesn’t go into the particulars that I would like to explore.

Yes, the Politico article in someways scooped a theme I have been working on for sometime on this blog. In the past I have been exploring the formation of political environments and asking “Do Campaigns Really Matter?”

Time for Change Model – Predicting POTUS elections

There are many reasons for developing and using models. Often models are used to present a hypothesis in a clear manner. We argue about models, back test them, refine them, and then use them to predict outcomes.

One of the most interesting models in Presidential elections is Alan Abramowitz’s Time for Change Model based on what is now referred to as the campaign fundamentals. Abramowitz has since revised his model, and we will look at both versions of the models.

The first Abramowitz model was:

PV=47.3+(.107*NETAPP)+(.541*Q2GDP)+(4.4*TERM1INC)

- PV stands for the predictive share of the majority party vote of the incumbent president

- NETAPP stands for the incumbent president’s net approval rating (approval-disapproval) in final Gallup poll in June

- Q2GDP stands for the annualized growth rate of real GDP in the second quarter of the election year, and

- TERM1INC stands for the presence or absence of an first term incumbent in the race

“This basic model has correctly predicted the winner of the popular vote in the last 5 presidential elections with an average error of 2 percentage points.” -Abramowitz

So, why change the model?

Because in the last 4 Presidential elections, the basic model overestimated the winning candidate’s share of the votes. “This suggests that the growing partisan polarization is resulting in a decreased advantage for candidates favored by election fundamentals including first term incumbents.: – Abramowitz

The revised Abramowitz model is:

PV=46.9+(.105*NETAPP)+(.635*Q2GDP)+(5.22*TERM1INC)-(2.76*POLARIZATION)

- POLARIZATION – takes on the value of 1 when there is a first term incumbent running or in open-seat elections when the incumbent president has a net approval rating > 0; it takes on a value of -1 when there is not a first-term incumbent and the incumbent president has a net approval rating <0.

“Adding the Polarization correction to the model substantially improves its overall accuracy and explanatory power” – Abramowitz

FRIENDLY REMINDER: The outcome is determined by the electoral college, not the popular vote predicted by this model.

Where does the model stand now?

NETAPP – the net approval of President Obama

If we look at Gallup’s polling results for President Obama’s Approval Rating – we can see currently it is +3%.

(What is surprising for most in Conservative circles is just how much the President’s net approval rating has been positive for his two terms. His average approval from the beginning of his first term to the writing of this post is 47%.)

Q2GDP (annualized growth rate of real GDP in the second quarter of the election year). The number obviously has not been released yet, but we can look at trends.

| GDP (% change from Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product) |

|

|

|

|

|

2013 |

|

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

2015 |

|

| Quarter |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

I |

II |

| GDP |

2.7 |

1.8 |

4.5 |

3.5 |

-2.1 |

4.6 |

5 |

2.2 |

-0.2 |

TBD |

TERM1INC – We know there is no incumbent in this election, so we KNOW this variable is 0.

POLARIZATION – We assume President Obama has a net + approval rating, so the variable will be set to 1.

Thought Exercise

While the model specifically states the GDP needs to be from Q2 of the election year (2016), as nerds we can have some fun.

If we were to perform the calculation now simulating an election this year with the following variables:

- using the current net approval rating of +3,

- the Average of the GDP Change over Obama’s term of +2.175%, (using the -.2 would be cruel)

- TERM1INC =0, and

- POLARIZATION = 1,

we calculate the incumbent party (Democrat) predicted vote % to be 45.8%.

| Variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NETAPP |

3.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q2GDP |

2.18 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q2GDP Increment |

0.50 |

ignore |

|

|

|

|

| TERM1INC |

0 |

Presence or Absense of Incumbent (1 Incumbent, 0 no incumbent) |

|

| POLARIZATION |

1 |

1 – first time incumbent or in open seat incumbent appr >0, = -1 no first time incumbent and incumbent approval <0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PV=46.9+(.105*NETAPP)+(.635*Q2GDP)+(5.22*TERMINC)-(2.76*POLARIZATION) |

| PV=party of incumbent % |

46.9 |

(.105*NETAPP) |

(.635*Q2GDP) |

(5.22*TERM1INC) |

(2.76*POLARIZATION) |

Estimate Q2GDP |

| 45.8 |

46.9 |

0.3150 |

1.3811 |

0 |

2.76 |

2.18 |

Abramowitz Model

Below is an interactive model that we can explore, plugging in your own variables.

Type in the yellow boxes and the sheet will give you the results – (incrementally increasing the GDP by the variable you provide)

The Abramowitz Time for Change Model is also inserted on a clean page all to reduce clutter for your enjoyment.

Ramifications

PV=46.9+(.105*NETAPP)+(.635*Q2GDP)+(5.22*TERM1INC)-(2.76*POLARIZATION)

As you can see, the model weights the GDP much higher than the net approval rating (by a factor of 6x), but the power of incumbency is considerable.

The model provides the incumbent party with a base of 46.9%, then adjusts for Net Approval, then adjusts for GDP, then adjusts for incumbency advantage/incumbency fatigue.

For example, if President Obama is +8 on Net Approval, the GDP change would need to be +8% change in Q2 2016 for the incumbent, Democrat party to break 50% with no incumbent running. (Note don’t forget to change TERM1INC variable to 0)

Admittedly, it is too early to use a model that explicitly states it is Q2 of the election year, but we can clearly remember Carville’s “It’s the economy stupid!”

If you believe the model, the next 12 month’s events are critical in determining the 2016 outcome and there is little the 40 people running for President can do about it – except drive down the net approval rating of the President. Get ready!

Ramifications for Local Elections

As we observe with my prior posts, Politico’s article, and the exploration of Alan Abramowitz forecasting model, the central thesis is this: the political environment is formed for success or failure well before any candidate announces a run for office. Campaigns do not change political environments but rather are a product of them.

These macro fundamentals are largely out of the control of Presidential candidates and even more so out of the control of state and local candidates.

However, local political environments can be shaped with local issues with a dedicated and consistent effort. Therefore, I’ll say it again: Attention all interest groups and political actors interested in the upcoming local elections: To be strategic in local elections, the time to form the political environment is a year before the elections, not the 6 weeks of a campaign before the election date.

by Alex Patton | May 26, 2015 | Political Research

An astute listener to the radio show, the Ward Scott Files, that deals with political strategy and polling asks, “What causes bumps in polling?”

Bumps in Polling

Often after a candidate announces they are running for President, or after a major party’s political convention or some other major event, we will observe a bump in polling numbers. In most cases, if we wait several weeks, the bump will disappear.

What are we actually observing with these “bumps” in polling numbers?

In an attempt to further answer the question, I came across a paper, “The Mythical Swing Voter” by Andrew Gelman, Sharad Goel, Douglas Rivers, and David Rothschild of Columbia University, Stanford University and Microsoft Research.

Political scientists have debated whether swings in the polls are a response to campaign events or are merely reversions to predictable positions as voters become more informed about the candidates (page 2)

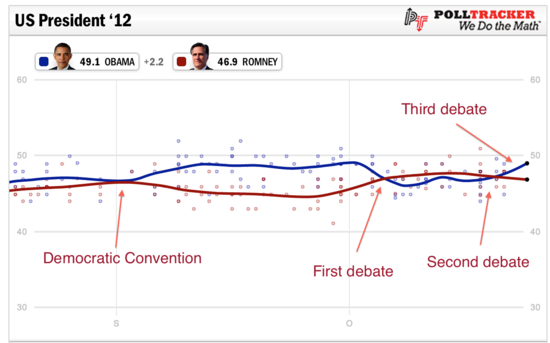

The paper follows an interesting methodology in that it conducted 750,148 interviews with 345,858 unique respondents on the X-box gaming platform during the 45 days preceding the 2012 Presidential election – creating a large on-line panel for studying shifts.

What is interesting is that the data showed with demographic adjustments, the data reproduced swings found in media polls during the 2012 campaign. HOWEVER, if we don’t use demographics, but instead use partisanship and ideology “most of the apparent swing in voter intention disappear.”

What the authors found was selection bias playing a role in the “bumps” candidates receive after a large announcement, meaning certain groups of people were much less/more likely to participate in a survey, and if we correctly estimate voters using items other than demographics, most of the apparent swings were sample artifacts, not actual change.

Only a small sample of individuals (3%) switched their support from one candidate to another.

We estimate that in fact only 0.5% of individuals switched from Obama of Romney in the weeks around the first debate, with 0.2% switching from Romney to Obama.

Conclusion(s)

The paper’s authors conclude “that vote swings in 2012 were mostly sample artifacts and that real swings were quite small.”

In today’s highly polarized partisan politics, the percentages of the Mythical Swing Voter is much smaller than polling would indicate.

Meaning, there is little to no actual bump or people switching sides – there is more of a selection bias in the polls. “The polls do indeed swing—but it is hard to find people who have actually switched sides.” (page 2)

The temptation to over-interpret bumps in election polls can be difficult to resist, so our findings provide a cautionary tale. The existence of a pivotal set of voters, attentively listening to the presidential debates and switching sides is a much more satisfying narrative, both to pollsters and survey researchers, than a small, but persistent, set of sample selection biases.