Affect, Not Ideology: Why We Loathe the Other Side (And It’s Not About Policy)

Let’s continue our exploration of polarization.

If you missed some of our previous posts here is a recent list:

- Affective Polarization and Misinformation Belief

- Intra-party fighting – family spats or real anger?Affective Polarization Within Parties: When Partisan Rivals Dislike Each Other More Than the Opposition

It’s everywhere, right?

We’ve all been there: scrolling through social media and seeing that one post that makes your blood boil.

You know, the one from your uncle who insists peas bleong in guac (which, by the way, they do not). Or better yet, it’s political — and you’re ready to unfriend or block half of your family and some of your friends over their latest rants.

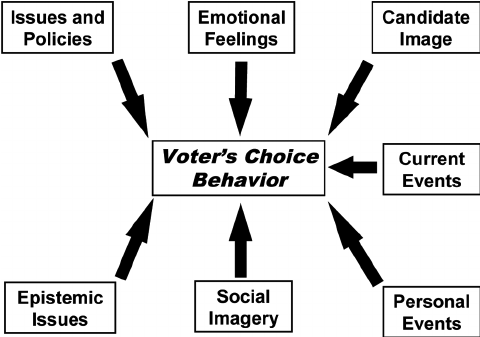

If you have ever witnessed me speak on politics, you have heard me discuss the overwhelming role emotions and affect play in our political process. It about emotion, NOT your 10 point detailed policy plan. PERIOD.

Now, we come across research that explores the question, and guess what – the growing divide between Democrats and Republicans isn’t actually about policy differences. According to the academic research we’re about to dig into, it’s about affect, not ideology.

Risking confirmation bias and an entire cup of “I told you so”, let’s explore this research.

Title: Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization

Link: Link to pdf of study

Peer Review Status: Yes

Citation: Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes. “Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76.3 (2012): 405-431.

Introduction

We’ve been told political polarization is all about policy — left vs. right, conservative vs. liberal; and every graduate political science student has had to write a paper on “Just how divided is America, really?” picking a side between Abramowitz and Fiorina.

But Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes ask us to pause. They argue that what’s really driving the wedge isn’t our stances on healthcare or taxes; it’s our feelings about the other party.

The team explores whether polarization comes more from affect (emotion and how much we dislike the other party) rather than ideology (our policy positions).

Spoiler alert: it’s more about emotion than reason.

Methodology

The researchers used a variety of surveys to dig into how Americans feel about opposing political parties. They relied on data from the American National Election Studies (ANES), among others, to track political attitudes from 1960 to 2010.

With thousands of respondents, their sample size is large and robust.

These surveys measured people’s feelings toward their own party and the opposing one, often using “feeling thermometers” to gauge how warmly or coldly participants felt about each party.

Results and Findings

Here’s where things get interesting (and a bit sad).

The findings show that over time, partisans’ feelings toward their own party have stayed pretty stable. People consistently rate their own party with a warm 70 out of 100.

But the real change? Their feelings toward the other party. The ratings for the opposing party have plummeted — falling by an average of 15 points since the 1980s. And in 2008, the average out-party rating dropped to just above 30.

Here’s the kicker: These negative feelings are based less on actual policy disagreements and more on a sort of tribal instinct.

The mere fact that someone identifies with the “other” side is enough to evoke a strong, negative reaction.

In fact, partisan animosity in the U.S. now exceeds divisions based on race or religion.

That’s right — we’re more divided by politics than by deeply ingrained social identities.

Critiques of the Research

While this study gives us a lot to chew on, it’s worth noting a few limitations.

First, the surveys mostly focus on attitudes in the U.S., so the findings may not be as generalizable to other countries with different political systems.

Additionally, the research was published in 2012 and uses historical data, it’s possible that modern changes in media consumption (like the rise of social media) might have further intensified these trends, something not fully captured in the study. This is an area for replication and a refresh.

Another area worth exploring? The impact of local vs. national political climates. Does the intensity of local elections, for example, ramp up partisan hatred, or is it more about presidential campaigns and 24/7 news cycles? Is all politics local or have all politics become nationalized?

Finally, could this be a function of partisans’ already sorting and being asymmetrically aligned on most major issues therefore looking for other reasons to be at each other throats? While the authors suggest that affective polarization—disliking the opposing party—is not primarily a product of ideological differences on policies. Instead, it appears to be driven more by social identity dynamics rather than by policy and affect polarization is distinct from policy polarization, a further exploration of causality would be interesting.

Regardless, polarization is likely driven by affect first. My experience is it is emotion first, not policy.

Conclusion

So, what’s the takeaway here? Partisan polarization isn’t just about ideological divides or policy arguments — it’s personal. We don’t just disagree with the other side; we dislike them, and that dislike has deepened over time.

As campaigns get nastier, and media outlets cater more to their partisan audiences, this trend is likely to continue.

But, if you ask me, maybe we should all just take a deep breath, share a scotch, beer, and/or a class of wine, and try to listen more than we dislike.

We don’t just disagree with the other side; we dislike them, and that dislike has deepened over time.

As campaigns get nastier, and media outlets cater more to their partisan audiences, this trend is likely to continue.

But, if you ask me, maybe we should all just take a deep breath, share a scotch, beer, and/or a class of wine, and try to listen more than we dislike.