The Audacious Public Affairs Playbook: What Bold Tactics Are Being Used

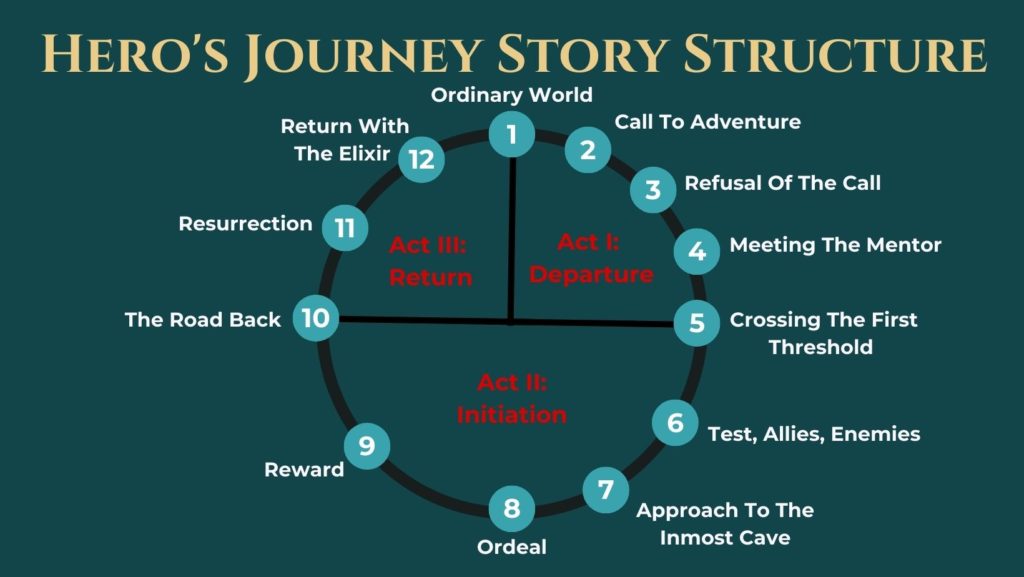

In political theory, two dominant models attempt to explain how power and public policy are shaped within a democracy.

The first is pluralism, the idea that a diverse array of interest groups competes within the political arena, with policies emerging as a compromise reflecting the public’s competing demands.

The second is elitism, which argues that a small, concentrated group of individuals or entities—typically those with significant economic or institutional power—dominates decision-making, often to the exclusion of broader societal interests.

But, as they say, “all models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Reality is rarely so clear-cut. Enter elite pluralism, a hybrid model that offers a more nuanced perspective. This theory acknowledges the competitive nature of pluralism but emphasizes that not all interest groups are created equal. While many groups may vie for influence, certain “elite” groups—those with disproportionate access to resources, networks, and institutional power—inevitably hold a stronger hand.

Elite pluralism explains why some voices, despite the principles of democratic competition, resonate more loudly in the halls of power. It’s not just about having a seat at the table; it’s about owning the table—or at least the most valuable seats around it. While competition exists it is just not a fair fight among equals.

Well-resourced groups have mastered this interplay between pluralism and elitism, creating systems where competition seemingly exists, but the winners are often predetermined. The audacious tactics they use to shape policy and public opinion are worth exploring.

NOTE: In this blog post, I am not making a normative argument. My aim is to acknowledge the tactics I have witnessed—and at times employed—in public affairs. It is up to you, the reader, to draw your own conclusions about the morality of these practices and their intersection with the First Amendment rights to free speech, petitioning the government, and assembly.

NOTE: In this blog post, I am not making a normative argument. My aim is to acknowledge the tactics I have witnessed—and at times employed—in public affairs. It is up to you, the reader, to draw your own conclusions about the morality of these practices and their intersection with the First Amendment rights to free speech, petitioning the government, and assembly.

“Any man who tries to be good all the time is bound to come to ruin among the great number who are not good. Hence a prince who wants to keep his authority must learn how not to be good, and use that knowledge, or refrain from using it, as necessity requires.” ― The Prince

The Audacious Public Affairs Playbook

A deeper dive into tactics used to shape the political battleground by any means necessary.

Machiavelli is often misquoted or misunderstood as saying, “It is better to be feared than loved.” That’s not exactly what he wrote.

In The Prince, he actually wrote: “Whether it is better to be loved than feared, or the reverse. The answer is, of course, that it would be best to be both loved and feared.”

However, he acknowledged that ideal conditions rarely exist, and when forced to choose, one should resort to being feared. Why? Because people are fickle. Love persists only as long as it aligns with self-interest, but the fear of pain and punishment remains constant.

In the world of public affairs, these principles are alive and well. I’ve generally categorized the tactics in the audacious playbook into two main camps: Buying Your Love or Beating It Out of You.

“Buying Your Love” Public Affairs Tactics

Tactic: Campaign Contributions & PACs

Financial support for political candidates or causes can buy access, influence, and loyalty. Well-resourced groups often make substantial donations to ensure that their voices are heard in the policy-making process. This is especially true in the era of super pacs and in the wake of the Citizens United decision.

Example: Elon Musk spends $277 million to back Trump and Republican candidates

Example2: Why some California Democrats take Big Oil money and vote against environmental laws

Tactic: Astroturfing

Creating the illusion of grassroots support to sway public opinion or influence policymakers. By creating a citizens group with little no to citizens “public” support can be seemingly manufactured for a cause, and groups can seem more popular or legitimate than they truly are.

Example: Microsoft accuses Google of secretly funding regulatory astroturf campaign

Tactic: Lobbying

Direct interaction with lawmakers, regulators, and government officials to push for favorable policies. This often involves offering expertise, research, and sometimes personal incentives to sway decisions. For example, the pharmaceutical industry spent $293,701,614 in 2024.

Example: Lobbying Data Summary

Example2: Lobbying Top Spenders by Sector

Example3: Lobbying Top Spenders by Industry

Tactic: Think Tanks & Research Funding

Well-resourced groups can fund research from “intellectually” aligned groups or universities, or even establish think tanks to produce research supporting their agenda. These tactics lend credibility and shape public discourse by presenting biased information as fact.

Example:The Secret Donors Behind the Center for American Progress and Other Think Tanks

Example2: Public Universities Get an Education in Private Industry

Tactic: Partnerships with Charities or Foundations

Donations to charitable organizations or foundations can help create positive public relations, align with a specific cause, and gain goodwill among key stakeholders. This can also be a form of indirect influence and sometimes leads to implicit quid pro quo.

Tactic: Revolving Door Employment

Hiring former government officials to serve in advisory roles or as lobbyists. This builds connections and ensures that former decision-makers continue to champion the interests of the group they once regulated.

Example: Video: Jack Abramoff: The lobbyist’s playbook on 60min

Tactic: Cultural Influence

Sponsorships and partnerships with media outlets, celebrities, and influencers can shape public opinion and create a favorable cultural narrative around the group’s goals.

Tactic: Political Endorsements and Strategic Alliances

Aligning with influential political figures or organizations can boost credibility and secure powerful allies in decision-making.

Example: LeBron James Shares Strong Political Message On New Nike Sneakers

Example2: Harris Grabs Green New Deal Network Endorsement That Eluded Biden

Example 3: Fossil fuel firms ‘spent £4bn on sportswashing’ says report

Tactic: Event Sponsorships

Hosting or sponsoring high-profile events (e.g., policy conferences, galas) to gain access to influential stakeholders and enhance visibility.

Tactic: Educational Initiatives or Scholarships

Funding educational programs or scholarships that align with policy goals to build goodwill and influence future thought leaders.

Example: Koch Foundation Criticized Again For Influencing Florida State

“Beating it Out of You” Public Affairs Tactics

A quick note on the use of the “dark arts” in public affairs: Sponsoring groups rarely engage in these tactics directly (especially if they are a public company). Instead, they often employ a layered strategy.

The key is to establish plausible deniability by structuring operations through cutouts often consultants and/or trade associations. By creating multiple layers, those funding the efforts (often to the tune of millions of dollars) can testify under oath that while their money may have been used to advance their interests, they had “no knowledge” of the specific tactics or details. They can then claim with a straight face, “Yes, we spent millions. We also always follow the law at XYZ group, have a dedicated compliance department, and firmly believe in our right to participate in the political process. We control no 501c(4) nor do we have a record of ever funding said group. XYZ has broken no laws.”

“So far as he is able, a prince should stick to the path of good but, if the necessity arises, he should know how to follow evil.” ― Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

Tactic: Opposition Research

In-depth digging into the backgrounds, records, and personal lives of political opponents or critics. This can be used to discredit individuals, create scandal, or shift public opinion against adversaries.

Example: Definers tries to reboot after Facebook oppo research controversy

Tactic: Corporate Espionage

In some cases, organizations may resort to stealing trade secrets, confidential information, or engaging in sabotage to gain a competitive or political edge.

Tactic: Smear Campaigns

Negative campaigning or information warfare designed to destroy reputations, spread misinformation, or stoke fear. This can be targeted at individuals, organizations, or entire movements that oppose the group’s interests.

Example: Facebook resorts to old smear tactics against TikTok

Example2: Facebook exposed in Google smear campaign

Tactic: Threats of Retaliation

Using threats, whether economic (such as pulling investments) or political (such as targeting re-election campaigns), to punish or coerce opponents into submission. The old “you’ll never work in this town again” threat.

Example: Trump has made more than 100 threats to prosecute or punish perceived enemies

Tactic: Legal Pressure and Litigation

Filing lawsuits or using the legal system to intimidate or financially drain opponents. Well-resourced groups may use legal battles as a form of harassment, knowing that smaller groups lack the resources to fight back.

Example: Frivolous suits stalk journalists in states without anti-SLAPP laws

Example2: Appeals court upholds Rick Wilson win over Michael Flynn in defamation case

Tactic: Astroturfing as a Coercive Tool

While also used to manufacture support, astroturfing can be deployed in a more aggressive form to attack and drown out opposition voices, overwhelming public discourse with misleading or false narratives.

Example: Mad at MADD

Tactic: Media Manipulation

Using media to create fear, confusion, or resentment toward certain groups, issues, or individuals. This can include planting stories, leaking confidential information, or directly influencing journalists to push a particular narrative.

We are now in the phase with media becoming so fractured that certain organizations are attempting to purchase media outlets outright or fund them via advertising / sponsorships as to co-opt any ‘journalistic’ standards.

Example: Powerbrokers: How FPL secretly took over a Florida news site and used it to bash critics

Example: In the Southeast, power company money flows to news sites that attack their critics

Tactic: Monetary and Economic Leverage

Threatening to withdraw funding or financial support from entities that don’t align with the group’s interests. This tactic uses economic influence as a means of forcing compliance or silence.

Example: Harvard and UPenn donor revolt raises concerns about big money on campuses

Tactic: Political Bullying and Intimidation

Using the power of government or other institutional levers to punish or pressure opponents. This can involve public shaming, threats of regulatory crackdowns, or direct threats of political retaliation.

Tactic: Straight Up Bribery

The direct exchange of money, gifts, or favors to secure a specific action or decision from a government official, policymaker, or other influential figure. R real quid pro quo. While illegal in most democracies, bribery remains a clandestine tool used to bypass traditional lobbying and advocacy efforts when outcomes are deemed critical or urgent by well-resourced entities. (and now thanks to SCOTUS, it appears you can have a winky winky agreement and then tip after.)

Example: Indian billionaire Gautam Adani’s business empire at risk amid U.S. indictment for fraud, bribery

Conclusion: Understanding the Audacious Public Affairs Playbook

This audacious public affairs playbook is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive. It highlights the lengths to which well-resourced groups can and will go to influence policy, perception, and power. Some tactics operate within the bounds of the law, others test its limits in legal gray areas, and a few are outright illegal. Many fall into ethical gray zones, while others blatantly cross ethical lines.

In an ideal democracy, every voice would be heard equally. Yet, as elite pluralism demonstrates, the reality is far more complex. Influence, access, and resources skew the playing field, often leaving ordinary citizens to compete against entities with disproportionate power.

Whether you admire or detest the tactics in this playbook, they reveal the raw, realpolitik side of public affairs.

However, don’t become too cynical. History is full of examples where less-resourced efforts have defied the odds to harness public opinion and achieve policy or political victories. Often, these successes come in reaction to a well-resourced group overplaying its hand or through decisive legal action.

While power and resources undeniably play significant roles in public affairs, they are not invincible. Just as the casino doesn’t win every time…..luck and timing can lead to a winning hand. However, continuing the casino metaphor, over time, the odds remain stacked in favor of the well-resourced. And like in a casino, the house usually wins.

As you reflect on these methods, ask yourself: Where do you draw the line between strategy and manipulation? Between fair competition and coercion? Public affairs, like democracy itself, demands constant vigilance, active participation, and critical scrutiny to ensure it serves the public good.

What’s your take? Are these tactics necessary evils, or do they erode trust in our institutions? Most importantly, what was left out?

PS. We must pay homage to two of the biggest contributors to the playbook.

The original OG: The Tobacco Industry

Then the Energy Industry took tobacco’s playbook and improved upon it.