by Alex Patton | Jan 11, 2018 | Ozean Media

I was asked yesterday “Whatcha reading?”

Here is the 2017 Q4 Reading list:

- Principles by Ray Dalio- GREAT business/life book. I wish I would have read it before I ever started any businesses.

- The Drunkard’s Walk by Leonard Mlodinow – A look at how randomness, probabilities, and uncertainty affect our lives.

- How Not to Be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking by Jordan Ellenberg – A dense read about math, decision making, and thinking. I need to re-read this one, but I enjoyed the challenge and the writing. Been chewing on the concepts for weeks.

- On Writing by Stephen King – part autobiography, part how to write, part how to edit (with examples), part how to structure your work, and part screed against adverbs. At times, hilarious. Easy read, enjoyed very much.

- Rat F**ked by David Daley – about the most political process known to politics: the process of drawing political districts. Remember: one party’s map is another party’s gerrymander.

- Slingshot: The Defeat of Eric Cantor by Lauren Cohen Bell and David Elliot Meyer- a deep dive into the Cantor defeat/Brat win. Short, accessible, and must read for political nerds.

- Break Your Invisible Chains: Own The Power Of Your Story by Brandon Telg, Jaron Jones, Carly Barnes – local Gainesville authors about storytelling. Offers writing prompts on how to tell your story and the importance of stories.

Book Awards:

Most Enjoyable Read: On Writing

Read that has stayed with me for weeks: How Not to Be Wrong

Need to Read Again: How Not to Be Wrong

Most relevant to political nerds – Slingshot

Book(s) I wished I read much sooner: TIE: Principles / How Not to be Wrong

Best Title: Rat F**ked

note: The links on this page are NOT affiliate links and are provided for your convenience.

by Alex Patton | Oct 26, 2017 | Ozean Media

A long time ago, we were going to change the world. We decided we had enough of that stuffy corporate world with its salary, benefits, and ample cash flow. We thought we had a good business plan, we thought we had completed the research – and we jumped. We started our own company, and damn it we were going to change the world.

Now, what to call this company?

Our brainstorming led us to German words.

The two founders of the company had strong ties to Germany – specifically Heidelberg, Germany. Alex Patton, Ozean’s co-founder, attended high school in Heidelberg (go lions!), and Ozean’s other founder was born in Heidelberg.

As a side note, Heidelberg, Germany is beautiful, and you should visit!

Ahh…inspiration was taking over.

Several rounds of brainstorming later, we came across “Ozean”. Ozean made PERFECT sense to us.

“Ozean” is the German word for “Ocean.” O•ze•an, pronounced Ozean!

THEN inspiration met cockiness – we were going to change the world by “making waves”….

BOOM! A company was named, a logo made complete with waves, and a brand birthed.

Fast forward years later, and I still get asked: “What is an Ozean?”, “How in the world did you come up with that name?”, “Can you spell that?”

At times, I wondered if we should have just named the company “AAAA Communications” and been done with it.

It begs the questions, “Do you name a company for personal reasons, name it for your potential customers, or does it really matter?”

In this case, every time I am asked, I explain the origin story. I would like to think it is somewhat memorable.

Regardless of whether it is memorable or not, the name is meaningful to us.

I’d like to believe we have matured from “making waves” to “Navigating to Victory – even the hard ones” but that evolution story is for another day!

Well, now you know….the origins Ozean. – a name inspired by Heidelberg, Germany, and cockiness (maybe naiveté).

PS. You really should plan a trip to Heidelberg, you’ll thank us!

by Alex Patton | Sep 21, 2017 | Political Media

Admittedly, I have been slacking in writing. This is due to workload and frankly falling off the writing wagon.

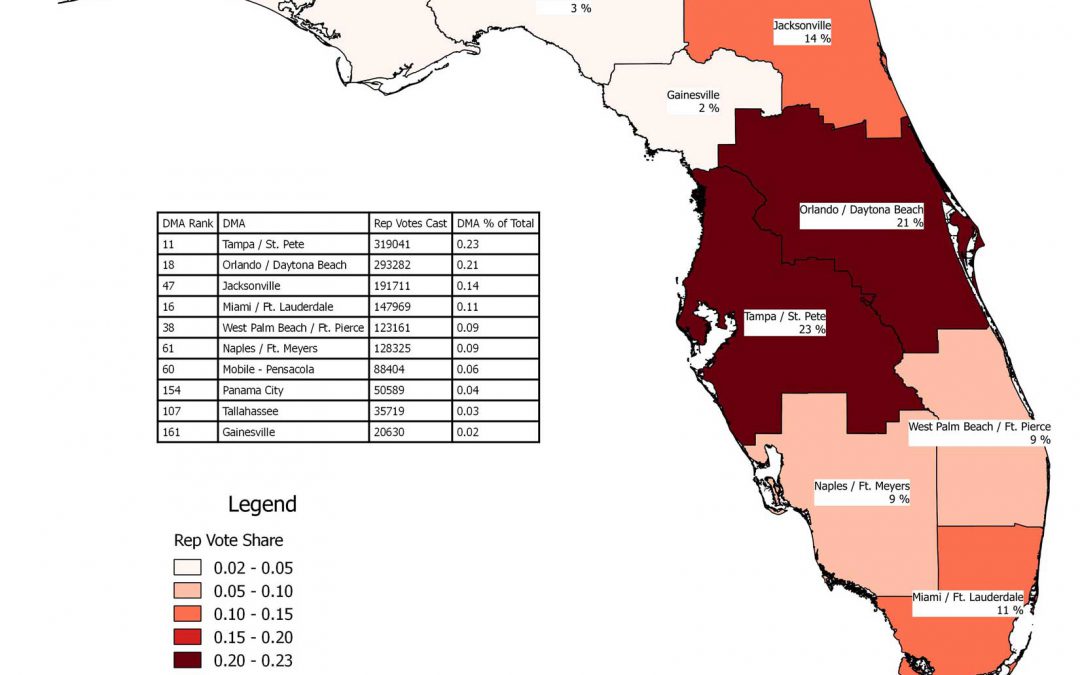

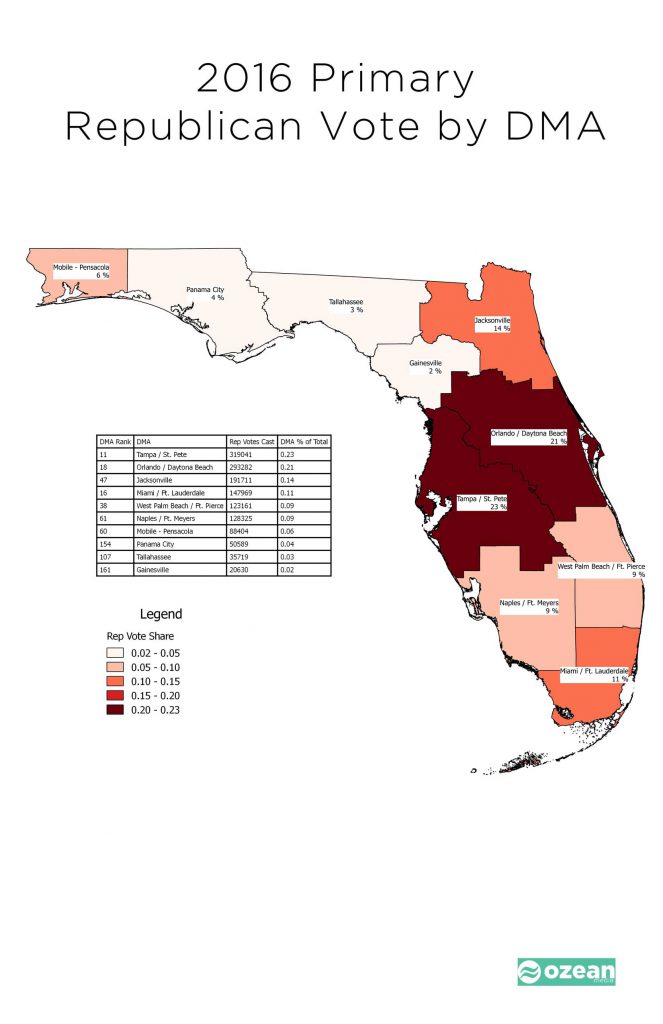

I will try and do better, but in the meantime, I was asked to look at Republican Turnout in Florida. I only explored those voters currently registered in Florida that voted in the 2016 primary.

I only explored those voters currently registered in Florida that voted in the 2016 primary.

I chose to look at the turnout by Florida DMA – and you see the critical nature of the heralded I-4 corridor. Nearly 1 out of every 2 Republican primary votes came from the Tampa/Orlando DMAs. On the flip side, there is the poor old Gainesville DMA. (No wonder we are ignored and don’t get to see many cool TV commercials.)

Next on tap is to project the anticipated turnout for 2018 – that is a little more involved and not for publication.

Until next time, enjoy!

by Alex Patton | Apr 18, 2017 | Political Research

Thinking about 2018 with a potential matchup of Rick Scott v Senator Bill Nelson, I was messing around with scripts to combine data sets and came up with vote totals for the 2014 campaign for Florida Governor featuring Rick Scott v Charlie Crist by Florida DMA (Television Markets).

Here you go…..I may write later on what this possibly means for 2018, but for now, it is provided as is for your enjoyment.

by Alex Patton | Apr 1, 2017 | Political Research

I went to bed last night thinking about about DecisionDeskHQ’s attempt to make a nationwide precinct map. It is a challenging and cool project.

Thinking about this as I slumbered, I awoke wondering just ‘how divided are we in Florida at the precinct level’?

Thanks to the great state of Florida, we have precinct level results, and over morning coffee, I found my answer.

The answer: Pretty damn divided.

If you consider a precinct “competitive” if separated by 10% or less, then few Floridians live in precincts that are competitive – the median difference in the 2016 POTUS election is 28% in Florida.

Only 18% of Florida’s precincts had Clinton and Trump within 10% of each other.

OR

Almost half (46%) of Florida’s precincts resulted in the difference between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton being greater than or equal to 30%.

P.S. The data is below, and now you know what nerds do on Saturday mornings before their kids wake up.

DATA

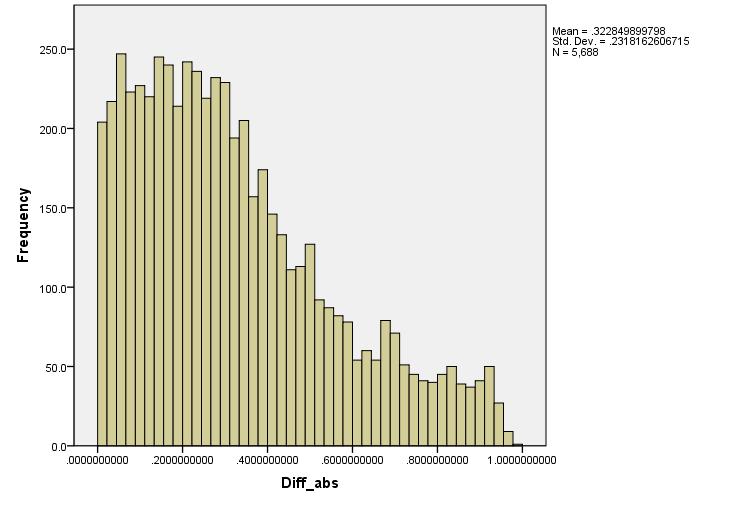

This is a histogram of the absolute value of the difference between the Clinton% and Trump% of the vote total.

Note: (I dropped the random precincts that are less than .01 and greater than .99)

Here are the summary statistics:

|

|

Cases |

|

| Valid |

|

Missing |

|

| N |

Percent |

N |

|

| 5688 |

100.00% |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Descriptives |

|

|

|

Statistic |

Std. Error |

| Mean |

|

0.32285 |

0.003074 |

| 95% Confidence Interval for Mean |

Lower Bound |

0.316824 |

|

|

Upper Bound |

0.328876 |

|

| 5% Trimmed Mean |

0.309017 |

|

| Median |

|

0.277699 |

|

| Variance |

|

0.054 |

|

| Std. Deviation |

0.231816 |

|

| Minimum |

|

0 |

|

| Maximum |

|

0.982301 |

|

| Range |

|

0.982301 |

|

| Interquartile Range |

0.315587 |

|

| Skewness |

|

0.804 |

0.032 |

| Kurtosis |

|

-0.083 |

0.065 |

Precinct by category

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| 0-10% |

1010 |

17.8 |

17.8 |

| 10-20 |

1033 |

18.2 |

35.9 |

| 20-30 |

1035 |

18.2 |

54.1 |

| 30-40 |

849 |

14.9 |

69 |

| 40-50 |

568 |

10 |

79 |

| 50-60 |

399 |

7 |

86 |

| 60-70 |

286 |

5 |

91.1 |

| 70-80 |

210 |

3.7 |

94.8 |

| 80-90 |

194 |

3.4 |

98.2 |

| 90-100 |

104 |

1.8 |

100 |

| Total |

5688 |

100 |

|

Sum of Votes cast by Precinct Category

| Category |

VotesCast |

% of total |

| 0-10% |

1739609 |

19% |

| 10-20 |

1732374 |

19% |

| 20-30 |

1920034 |

21% |

| 30-40 |

1454646 |

16% |

| 40-50 |

909401 |

10% |

| 50-60 |

578875 |

6% |

| 60-70 |

367632 |

4% |

| 70-80 |

225290 |

2% |

| 80-90 |

228293 |

2% |

| 90-100 |

121634 |

1% |

| Total |

9277788 |

100% |

You can download my cleaned data at: gitHub or at data.world.