I have been thinking a lot about thermostats and politics lately.

This thought pattern has been driven by two things:

- I banned someone from my facebook page for the first time ever, and

- Two separate books I have been reading discuss thermostats and politics.

The Facebook Ban

First, the facebook ban.

As you may know, I am a weekly guest on a local talk radio show. I discuss politics, political strategy, and the science behind politics. Over the past few months, I have ‘engaged’ in a ‘debate’ with a loyal listener.

I am all for free speech, debate, and the exchange of ideas. I enjoy it, I enjoy different perspectives, and I enjoy being challenged.

However, our ‘debate’ always seemed to denigrate with this listener to a bullying session rather than any attempt to learn from one another. The listener’s mind was made up, and if you didn’t 100% agree, began the attempt to beat you into submission with a volley of name calling, fallacies, and curated ‘proof’ from selected blogs.

The final straw was when the listener fabricated and attributed to me things I didn’t say in an attempt to make a point. Even when corrected, the listener wouldn’t stop. All of this being done mostly on my facebook timeline.

A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.

-Winston Churchill

Finally, I had enough of the nonsense, shrill rhetoric, and name calling. I banned the listener. It has been the most peaceful, glorious week.

Yes, you have a right to free speech, but I have a right to turn the channel.

However, the series of incidents served as a perfect, recent example of the overheated, political rhetoric of our times.

The Books

I have read two books in the past three weeks:

Schelling’s book, Micromotives and Macrobehavior, explores the relationship between individual’s decisions and their individual characteristics (micromotives) and aggregated social patterns (macrobehavior), and how these two influence each other. Because as we know from our previous studies, our observance of how people act is a powerful force on how we act. Schelling writes of ‘contingent behavior—behavior that depends on what others are doing.’

Ideology in America’s “main theme of this book, that when it comes to policy preferences, there are more liberals than conservatives. On average about 50% more Americans choose the liberal response (or the liberal end of a continuum) than choose the conservative response. Given a choice between left and right options for government activity, left prevails on average. And this pattern is robust. It will not matter what assumptions we make or what operations we perform. The picture will always be the same.”

So, one book about economics, the other book about political ideology and the disconnect in people’s stated political ideology and their policy preferences at an operational level of government.

When two separate and non-connected books (one authored by a Nobel prize winner) mention the same thermostat framework, it is time to place close attention.

Thermostats and Politics

The basic premises of both books is explained in Schelling’s Micromotives and Macrobehavior :

“The thermostat is a model of many behavior systems—human, vegetable, and mechanical.” (Schnelling)

“If the system is up to the task of attaining the desired temperature, it generates a cyclical process. The temperature rises in the morning to the level for which the thermostat is set—and overshoots it. It always does. The temperature then falls back to the setting—and undershoots it. It rises again and overshoots it. The house never just warms up to the desired temperature and remains there.” (Schnelling)

“The thermostat is smart but not very smart…. If the system is “well behaved” the ups and downs will become smaller and eventually settle on a steady wave motion whose amplitude depends on the time lags in the system.” (Schnelling)

Political Ideology, when writing about the study’s methodology expands this framework specifically to politics:

“In Wlezien’s conception, public opinion is mainly relative – a matter of more or less rather than absolutes.” (Ellis & Stimson)

“Public Policy Mood moves in the direction opposite to control of the White House and does so quite systematically.” (Ellis & Stimson)

“It tends to reach high points in either the liberal or conservative directions in the years in which out parties regain control. And then it moves steadily away from the winning and controlling party.” (Ellis & Stimson)

“Group A is left of Party “L.” Group B has preferences between the two parties. And Group C is to the right of Party “R.” But since only Group B changes in response to party control, it forms the longitudinal signal for the entire electorate. Thus the whole electorate acts, on average, as if it were entirely composed of Group B.” (Ellis & Stimson)

“Our conclusion is simple. Our best single understanding of why public opinion moves is that based on basic thermostatic response. Much political commentary, failing to take this fact into account, ends up looking to mystical and exotic sources to explain the commonplace. And much of that commentary sees the changes of the moment as harbingers of a different future, when the political landscape will be fundamentally different from what it currently is. But we know that the changes of the moment will be reversed as quickly as they came, as the public reacts against the ideological direction of the party in power.” (Ellis & Stimson)

Conclusions

Believe it or not, today’s extreme rhetoric can be explained as “normal” and in fact, completely predictable and expected.

In my opinion, today’s rhetoric is in response to two major items:

- the extreme nature of the recent financial meltdown, and

- the extreme nature of the expansion of government with Obamacare.

If you consider our political system to be explained by a ‘thermostat model’, today’s extreme rhetoric is simply Group C reacting in an attempt to regulate the political system.

Take solace that “Group B” will win- in time, and the system will regulate once again back towards some sort of equilibrium.

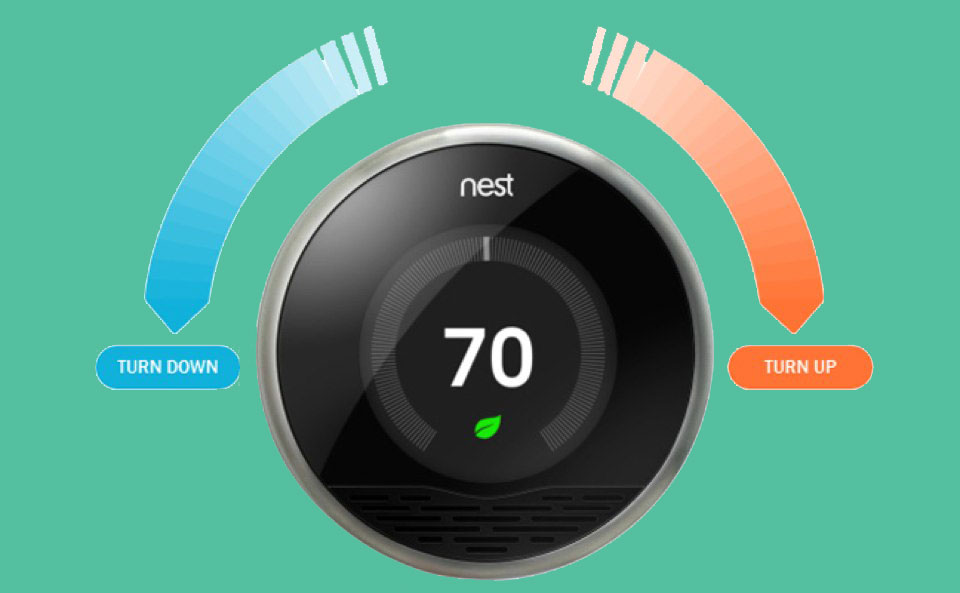

The Nest thermostat pictured above has gained a toehold in the market because the current thermostats are inefficient – our old thermostats aren’t that smart.

What America needs politically is a Nest thermostat, but until that time calm down and relax. Unfortunately, today’s shrill politics is an overheating of the system, soon to self-regulate.