There is a difference between descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. There is also a difference between the following two questions:

- What are my chances of challenging an incumbent? and

- If I decide to challenge an incumbent, what do I need to do to be successful?

Today, we explore second question.

If I decide to challenge an incumbent, what do I need to do to be successful?

People are upset and anxious and with these feelings comes the desire to throw out every incumbent, but that seldom happens. Why?

We are not going to explore the substantial advantages incumbents enjoy. We are going to set them aside and attempt to answer the question, “what does a challenger need to do to be successful?”

Often in politics, we borrow from other disciplines and blend them together. In attempting to answer this question, I am going to borrow heavily from business to build out a new theory on challenging an incumbent.

The specific theory I am going to use is the New Lanchester Strategy. The strategy has its roots in Britain and then used by Japan business as a closely guarded trade secret. The New Lanchester Strategy is considered one of the best tools available for determining market type choices for both start-ups and existing businesses and is used to formulate marketing plans with strategies to attack market share.

The theory has military, business and political implications.

The New Lanchester Strategy asks “How do you win customers for a new, improved offer? You must understand how customers decide, and you must target at their decision process. It means that the offered products or services must become irresistible for the target market.”

I came across the New Lanchester Strategy when reading The Four Steps to the Epiphany, by Steven Gary Blank. Mr. Blank is a founder of the lean start-up movement and the book is considered a classic book in the start-up world.

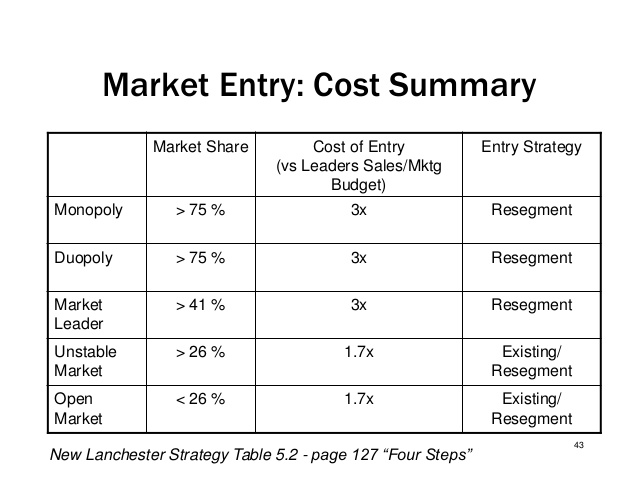

Mr. Blank removes the math and states:

- If a single company has 74% of the market, the market has become an effective monopoly. For a startup, that’s an unassailable position for a head-on assault

- If the combined market share for the market leader and second-ranking company is greater than 74% and the first company is within 1.7 times the share of the second, it means the market is held by a duopoly. This is also an unassailable position for a startup to attack.

- If a company has 41% market share and at least 1.7 times the market share of the next largest company, it is considered the market leader. For a startup, this too is a very difficult market to enter. Markets with a clear market leader are, for a startup an opportunity for re-segmentation.

- If the biggest player in a market has at least a 26% market share, the market is unstable, with a strong possibility of abrupt shifts in the company rankings. Here there may be some entry opportunities for startups or new products from existing players.

- If the biggest player has less than 26% market share, it has no real impact in influencing the market. Startups who want to enter an existing market find these the easiest to penetrate.

Blank adds two more important rules in the strategy that are particularly relevant:

- If you decide to attack a market that has just one dominant player, you need to be prepared to spend three times (3x) the combined sales and marketing budget of that dominant player.

- In a market that has multiple participants, the cost of entry is lower, but you still need to spend 1.7 times (1.7x) the combined sales and marketing budget of the company you plan to attack.

Political Implications of the New Lanchester Strategy

If we consider an incumbent politician as having established market-share, and if we switch market-share for favorability polling numbers or even elections results, we can start to apply the New Lanchester Strategy to politics and develop a substitute hypothesis.

I think the best substitute is favorability ratings because it should be more current than past election results.

I am going to over-simplify for a starting point.

- If an incumbent has a favorability rating over over 74%, it is an unassailable position for a head on-assault; possible with a strategy of re-segmentation.

- If an incumbent has favorability ratings between 41%-74%, it is still an unassailable position for a for a head on assault; possible with a strategy of re-segmentation.

- It is not until the favorability rating is less than 41%, do we observe an easier path to entry.

Blanks’s stunning finding using the New Lanchester Strategy: regardless of the specific market-share or favorability ratings, if you are going to challenge an incumbent, you need to spend 1.7 x – 3 x the communication budget of the incumbent to take market-share.

Conclusion

As a company that has run many challenges to incumbents, some successful, most not; it is difficult to explain to excited candidates the difficulties facing challengers – not even specific to your candidacy – but rather any challenger.

When challenging an incumbent, almost every card in the deck is stacked against the challenger.

Now, consider a political neophyte with no market-share.

Candidates often cite such events like Rep David Blat’s defeat of an Eric Cantor as proof of concept, but interestingly they never consider the true Black Swan nature of such a defeat.

Combine that fallacy with prospective incumbent challengers basing their campaign budgets on what either the incumbent or a previous unsuccessful challenger spent, and we have a recipe for defeat.

We are now going to take this new theory and back test it against races to where incumbents or politicians with high market-share (in open races) were defeated by successful challengers. Any bets whether this new theory holds true?

Our first case study will be Representative Curt Clawson’s win in Florida.

Additional Reading

New Lanchester Theory for Requirement Prioritization, Dr. Thomas Fehmann (PDF)

Lanchester Laws Apllied to Sales Campaign Succes by Paul McNeil (PDF)

The Four Steps to the Epiphany, by Steven Gary Blank (Amazon link, non-affiliate)